The Breaking String

(Posted 4-7-11)

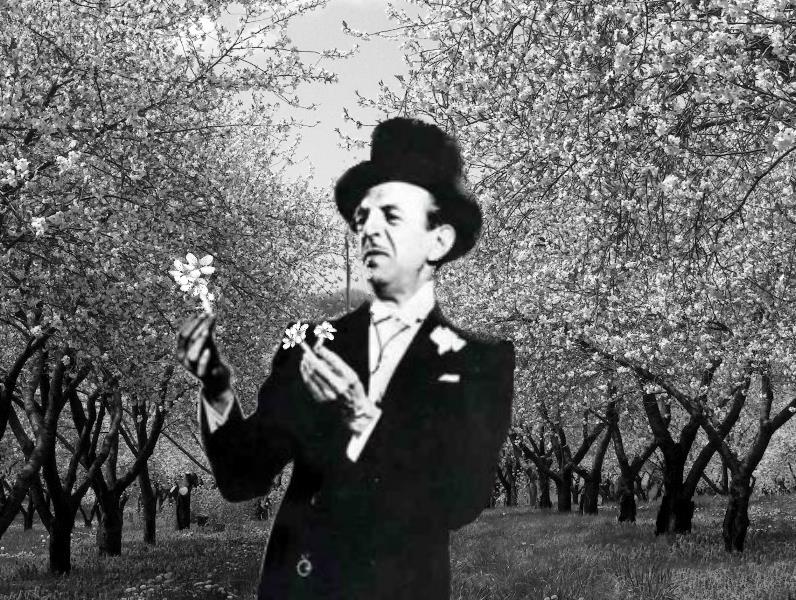

(Cardini in the Cherry Orchard)

It’s funny what you remember. Years ago I saw a production of Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard and today I could tell you just two things about it: 1) I think it was about a bunch of rich people who get really worked up about some trees and, 2) there’s a great moment where the characters hear a sound and each one has a different interpretation of what caused it. This is how Chekhov wrote it:

Suddenly a distant sound is heard as if from the sky, the sound of a breaking string, which dies away sadly.

LUBOV: What's that?

GAEV: Or perhaps it's some bird . . . like a heron.

TROFIMOV: Or an owl.

LUBOV: (Shudders) It's unpleasant, somehow.

That’s it. A little nothing of a scene, isn’t it? And yet I can’t tell you how many times I’ve thought of that scene since then. It has helped me as a writer dozens and dozens of times because we writers (like magicians) tend to focus on what our characters do – this scene reminds me of one the most revealing and yet neglected aspects of characterization: how a character reacts.

The different reactions these characters have to the same sound hints at their character without actually defining it. It doesn’t tell us what’s going on in their minds, but it gives us a peek and leaves us to work out how their answer makes sense within their overall characterization: why does this one think of a bucket, and that one a bird, this one a very different type of bird and the last one something undefined and foreboding? It makes them seem more vivid and real.

A couple years ago I wrote a script set in a haunted apartment – I started the script off with a short BOO! scene (set in the past), but then it made sense to have a scene where our protagonists, two young women who were moving to the city after college, are first shown the apartment.

Now in one sense, this is the kind of scene writers dread: how can you make it interesting? To be realistic means being dull. You could go quirky and have some crazy landlady dressed in headscarves and peasant skirt going on about the apartment’s weird history (ick). You could do one of those, “It seems too good to be true!” openings, where the renters can’t believe they’re getting such a good deal on such a great apartment which feeds our morality-tale-fueled expectations that the other shoe will soon drop – a much better solution, but it’s just been done so many times (eg. The Amityville Horror).

When I was grappling with how to deal with it, I thought of Chekhov’s breaking string –suddenly the scene came together for me: this is about the different ways these two women look at the apartment! Presumably the audience would know from the movie’s advertising that these women were our heroes – when they first walk onscreen the audience is curious: who are they? And the audience doesn’t want to be told the answer – they want to find out for themselves.

So here’s how I wrote the scene: after a brief description of the apartment and the Building Manager showing the room, I turn our attention to the protagonists (bear in mind that in screenplays brevity is vital):

CHRISTINE PRENTICE (20s), in loose jeans and a Raconteurs T-shirt, checks the multiple door locks carefully, but when she’s sure they’re sturdy, she wanders aimlessly, soaking up the space, imagining what she can do with it. She likes it.

EDNA KITE (20s), in designer jeans and T-shirt, small sparkly jewelry and a YSL tote, moves directly, logically from one place to the next as if she has a mental checklist. Edna eyes a brown stain on the wall and paint drops on the floor. She disapproves.

The scene goes on for another page with the same basic flavor – low key but giving us hints of character. The script subsequently sold to Phoenix Pictures (Black Swan, Shutter Island) and through all the many rewrites that little scene where the two women look at an apartment made it through virtually without change.

So what does Chekhov’s breaking string have to do with magic? Admittedly, it’s something that becomes more obvious when there is more than one character reacting to a single stimulus which isn’t the case in most magic shows. Unless you consider assistants from the audience to be characters (in a way, they are), or a magician’s assistant (indeed, using a woman assistant merely as a pretty prop strikes me as not just out-of-date gender stereotyping but a wasted opportunity to add a bit of real human drama/comedy to an act).

Once again, I think the central lesson of the breaking string is that it makes us focus on the power of reactions and this can manifest itself in a myriad of unexpected ways. Consider the two young women from my script and imagine that instead of walking into an apartment they are walking out on stage to do a magic show for an audience.

Imagine Edna slickly dressed, radiating professionalism, striding out on stage, acknowledging the audience with a confident wave but never veering from the straight line she makes toward the microphone. Getting there she realizes it is not set to the height she had asked for – she casts a little look off stage – no worries, but you’ll remember to get it right next time won’t you? Then quickly adjusts it and gets her job done.

Christine wears virtually the same clothes, but she wears them looser, more casually, without the accents. Before she goes on stage, she peeks out from behind the curtain, a little scared about what she might find. But when she sees the happy faces and hears the warm applause, her face lights up. She drifts out, soaking up this moment that will never happen again. She looks up at the rafters – man, that’s high – and smirks at the cheesy backdrop. When she gets to the microphone, it’s too high – she gets on her toes to speak into it, before realizing that’s kind of silly. She adjusts it as she giggles to herself.

To me this is much more vivid than merely walking out with confidence – it gives an audience a sense of who you are in a very economical way. Obviously, the difference in these two entrances would be more obvious if the two came out together, but I think an audience would still notice such subtleties in a solo entrance – after all, they’ve seen hundreds of entertainers walk out on stage before.

Or take an effect where the same stimulus, say a magical moment, happens repeatedly. I know back when I was young and did a lot of card magic, I probably didn’t give a second thought to how I reacted when the card appeared on top of the deck during the Ambitious Card trick – I was too concerned with how the audience reacted: were they amazed or did they catch me? I think if I ever decided to take up the effect again, the question of how the magician reacts to the magic would be central: here’s an effect where basically the same thing happens over and over. A good actor would see this as a tremendous opportunity to define his character, show his strengths and limits and chart his progression. Magicians generally focus so much on the progression of the effect – the plot – that they ignore how the character develops.

There is a lot to be gained by thinking about how you react when the magic happens. Cardini built his career on coming up with a new way to react to his own miracles: drunken befuddlement. That made a huge difference – I bet that back in the day there were a lot of people who had seen a whole bunch of magicians pull stuff out of the air during their lives who, years later, couldn’t bring any of them to mind except “that drunk guy in the tux”. Or consider David Blaine: certainly two of the biggest factors in his rise had to do with reaction: that odd stare he had when he did a trick and the way he highlighted the audience reaction by turning the camera on them.

A magician sets his own rules because when a miracle happens only he knows if it happened exactly the way he intended. A magician can therefore be cocky, befuddled, stunned, surprised, frustrated, amused or astounded by his effects. He can be all these things at different moments – as long as there is a clear internal logic to what he’s doing, the audience will go along for the ride. And if the characterization is vivid, that audience will be much more likely to remember that particular magician long after others have faded from memory.

Back to the Film and Magic Blog

©Chris Philpott 2011. All rights reserved. Original designs and content

by Kathleen Breedyk and Chris Philpott.

Contact Us .