Character and Plot in a Full Magic Show

Part Two: Plot

(posted 11/19//2011)

In magic we talk about tricks having plots and that seems reasonable to me. Certainly an ace assembly tells a little story of things coming together even without a superimposed narrative -- say the story of a family coming together. We just get it on an intuitive, archetypal level. Of course sometimes a superimposed story can be poetic and amazing -- think of Eugene Burger's "Gypsy Thread" -- but too often the trick and story are yoked together awkwardly and the trick itself is reduced to the level of an illustration in a bad children's book.

So if tricks are little stories is a magic show like a short story collection? And if it is, couldn't the magic show structure of one trick after another develop into something more grand and cohesive, the way medieval collections of stories evolved into collections with framing devices (like The Canterbury Tales), then stories centered on a single hero (picaresque novels like Don Quixote) and then the modern novel? Or maybe tricks are more like songs and a magic show like a concert. Sure, there's some structure to a concert -- start big and finish bigger -- but there's nothing like this:

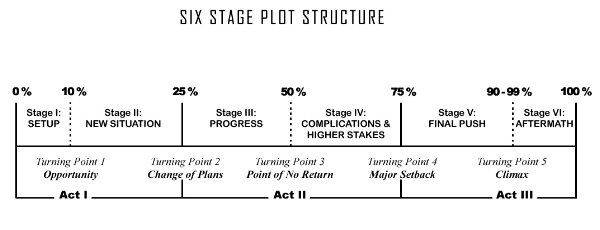

This is a well-known screenplay structure (there are a bunch but this is the one I use). It's by Michael Hauge and it fuses his inner hero's journey with the mythological structure Christopher Vogler outlined in The Writer's Journey. Vogler Hollywoodized Joseph Campbell's Hero with a Thousand Faces (a major influence on Star Wars). Campbell drew on Jung, who learned from Freud, who liked smoking cigars.

So can we take this structure and apply it to a magic show?

That’s a tricky one…

Truffaut wrote a great article about de Sica's The Bicycle Thief in which he said something to the effect that critics say the film is about the dehumanizing effects of poverty in post-war Italy, etc, etc, but it's actually about a guy who really, really wants a bicycle! It's true -- this film, like many films, is structured on a central desire. Our hero wants something and events conspire to keep it from him until the very end of the movie (Hollywood) or forever (Europe).

What's Jaws about? A big city cop who moves to a small town because he wants to feel safe -- he wants safety for himself, his family and his community -- but he eventually realizes that only by risking his own safety can he achieve his final goals. Right? No! It's about a guy who really wants to kill a shark! Now that's something you can show: shark eats someone at start, shark blows up at the end. You don't need Roy Scheider to say at the end "You know what? Now I finally feel safe."

And Walk the Line is about the life, times and artistic genius of Johnny Cash, right? No, silly! It's about a guy who really, really wants to get it on with June Carter!

I've come to think of structures like Michael Hauge's as less about organizing story and more about organizing desire. Two hours is a long time for someone to really, really want something.

Now here's the problem with applying his structure to a magic show: if I tear a newspaper to pieces, the audience may think, "Gee, that sucks. How's he gonna read it?" But then I restore it. Problem solved.

And if someone loses their card in a deck, they might think, "Wow. That card is lost. Damn." But then I find it. Adios desire. Next!

“In most magic, as far as I can see, the plot is, “I wish for something. I get it. And it’s what I want (though many right-thinking persons might well ask 'what earthly use does that raucous geezer have for a dove?')” The cause in this case is the magician’s will. He wills it: it comes true. This is not a drama about a human being. It is the depiction of a god, generally a capricious and trivial one. And it’s just as dull as the biography of any omnipotent being would be.”

-Teller, quoted in Derren Brown’s Absolute Magic.

So let me get back to Hollingworth and Zabrecky. Another reason Hollingworth comes off as emotionally cool has to do with desire -- his characters don't have any. They have no overarching goal they want to accomplish. They might have a certain passion for the pasteboards, but the audience is never really invited to partake of that since there is no narrative reason to do so. We sit back and watch an obsessive obsess with a kind of dispassionate fascination. It's very cool, in every sense of the word.

But Zabrecky's character really, really wants something all through the show: he wants to save the moon! Okay, that's an odd goal, but dammit, it works! It's strange, it's childish, it's borderline insane, but it's magical.

Adding a long narrative to a magic show is tough -- it requires rigor. It's like the difference between a concert, where the songs are paramount, and Walk the Line, where songs always serve the greater narrative goal. Each and every song in Walk the Line moves the story forward: Cash doesn't just sing "Folsom Prison Blues", it serves as the moment he proves himself to Sam Phillips and breaks through into the big leagues.

Similarly, when you add a narrative to a magic show, every trick has to move the narrative forward. You can never allow yourself to stop the narrative and just admire the beauty of a single trick. It's not a challenge every magician would or should want to take. I imagine Vernon would laugh at the very idea. But Zabrecky took on the challenge -- he's swinging for the fences here, guys.

That means trying out new things. There's a moment when, to save the moon, Zabrecky starts to dance. My heart leapt when he started to do that – it was just so goofy, so evocative, so right. Was it because there is so much lore connecting dance to the elemental forces of the world? (Moon dance, rain dance, sun dance, fire dance…) I guess that doesn’t hurt, but it’s not the thought that pops in your head as you watch – me, I was just thrilled: what a crazy, cool idea!

And yet, as the dance proceeded, the thrill tapered off -- I think because the act of dancing seemed to accomplish no practical goal. What goal could there be? I’m not sure but I was reminded of a scene in Twin Peaks where (as I recall) the hero tries to find a suspect by throwing rocks at a can -- with the first throw he says "A" and with the second "B" -- when he finally hits the can he knew the suspect's name began with that initial. No, it made no sense, but it was brilliant – it was dream logic. What better logic for a magic show?

These are not easy problems to solve but I think they are

the kind of questions that can lead to the development of the art of magic.

These are problems Doug Henning wrestled with when he put together The Magic

Show. These are problems the giants of the golden age of magic dealt with

in their full evening shows. These are problems that magicians like Rob Zabrecky,

Guy Hollingworth and Derren Brown are dealing with now and I’m excited

to be a witness to their wonderful work.

Go Back to Film and Magic Blog

©Chris Philpott 2011. All rights reserved. Original designs and content

by Kathleen Breedyk and Chris Philpott.

Contact Us .